- This article is about the bird. For the Phoenician king, see Phoenix (king).

The Phoenix (Ancient Greek: Φοῖνιξ (Phoînix)) is a mythical, sacred firebird that can be found in the mythologies of the Greeks, and Romans. The Phoenix may have been inspired by a similar creature from Egyptian mythology called the Bennu. In later time periods, Christians used the Phoenix as both an allegory of and proof for Christ's death and resurrection.

Appearance[]

The appearance of the Phoenix differs over time depending on the source. According to Herodotus, the Phoenix is an eagle-like bird with red and gold feathers. In Roman wall art, the Phoenix is depicted as having a crest similar to a peacock's. In Medieval Christian Bestiaries, the Phoenix was considered to be Phoenician purple in color, as an explanation for its name. The most extensive and imaginative description of a Phoenix comes from "The Travels of Sir John Mandeville," which was a supposed travel memoire written in the 14th century CE by an unknown author:

| “ | This bird men see often-time fly in those countries; and he is not mickle more than an eagle. And he hath a crest of feathers upon his head more great than the peacock hath; and is neck his yellow after colour of an oriel that is a stone well shining, and his beak is coloured blue as ind (indigo); and his wings be of purple colour, and his tail is barred overthwart (crosswise) with green and yellow and red. And he is a full fair bird to look upon, against the sun, for he shineth full gloriously and nobly.

-The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (pg. 33)[1] |

” |

In Mythology[]

The Phoenix is a mythical bird with colorful plumage that is said to be either from Arabia or India. There is only ever one Phoenix alive at a time. It has a 500 year life-cycle, near the end of which, it builds itself a nest of incense and sacred materials that it then ignites. The bird is then consumed by the fire of its nest, but from its ashes a young Phoenix arises, reborn anew. The newborn Phoenix is destined to live as long as its previous incarnation. In some stories, the new Phoenix embalms the ashes of its old self in an egg made of myrrh and deposits it in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis (literally "Sun-City" in Greek).

The Phoenix in Ancient Greek Sources[]

The earliest use of the term "Phoenix" is from a fragment of text attributed to Hesiod, who lived between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Within the text, Nymphs are measuring the length of their lifespans in units of Phoenix's lifespans in order to show just how long-lived they are. The point being that Phoenix's are particularly long-lived birds:

| “ | A chattering crow lives out nine generations of aged men, but a stag's life is four times a crow's and a raven's life makes three stags old, while the Phoinix (Phoenix) outlives nine raves, but we, the rich-haired Nymphai (Nymphs), daughters of Zeus the aigis-holder, outlive ten Phoinixes.

-Hesiod, Precepts of Chiron Fragment 3[2] |

” |

The Nymphs in the text above say that they can outlive ten Phoenixes. In later texts the general standard for the lifespan of a Phoenix is 500 years. When this standard is applied anachronistically to the Hesiod fragment, it translates that the Nymphs can live in excess of 5,000 years.

Herodotus' Histories[]

Herodotus, the Greek writer and Historian from the 5th century BCE, is the first to give a complete description of the myth of the Phoenix. In his famous work "Histories," written in 430 BCE, he states:

| “ | There is another sacred bird, too, whose name is Phoinix (Phoenix). I myself have never seen it, only pictures of it; for the bird seldom comes into Aigyptos (Egypt) : once in five hundred years, as the people of Heliopolis say. It is said that the Phoinix comes when his father dies. If the picture truly shows his size and appearance, his plumage is partly golden and partly red. He is most like an eagle in shape and size. What they say this bird manages to do is incredible to me. Flying from Arabia to the temple of the Helios (the Sun), they say, he conveys his father encased in myrrh and buries him at the temple of Helios [i.e. in the temple of the Egyptian god Ra]. This is how he conveys him: he first molds an egg of myrrh as heavy as he can carry, then tries lifting it, and when he has tried it, he then hollows out the egg and puts his father into it, and plasters over with more myrrh the hollow of the egg into which he has put his father, which is the same in weight with his father lying in it, and he conveys him encased to the temple of the Sun in Aigyptos (Egypt). This is what they say this bird does.

-Herodotus, Histories 5.73[2] |

” |

In Herodotus' description the Phoenix is a red and gold eagle-like creature that lives in Arabia and only comes to Egypt once every five hundred years in order to die and be reborn. When the Phoenix is reborn, it places its prior ashes in an egg made of myrrh, which is a sap-like resin derived from the myrrh tree. Myrrh was commonly used as an incense in ancient times. The Phoenix would then take the egg to the temple of Ra, which Herodotus calls "the temple of the Helios," giving the Phoenix solar associations. The dying and rebirth of the Phoenix could by symbolic of the continual "dying" and "rebirth" of the sun.

The Phoenix and the Bennu[]

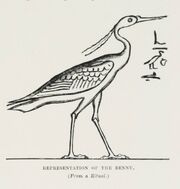

A drawing of the bennu based off of Ancient Egyptian depictions, from "Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque (Volume 1)," By Georg Ebers (1878)

The associations with the sun, the Egyptian god Ra, and the city of Heliopolis has lead scholars to believe that Herodotus may have been relaying the myth of the Bennu bird from Egyptian mythology to his primarily Greek audience.[3] The Bennu, was the sacred bird of the city of Heliopolis, and was considered to be the manifestation of the soul of the solar god Ra.[3] But rather than being an eagle like the Phoenix, the Bennu was a type of large, now extinct, Heron (Ardea bennuides) whose fossils were discovered in modern-day United Arab Emirates.[3][4] The Bennu is believed to have become extinct sometime around 2500 BCE.[5]

The Phoenix in Ancient Roman Sources[]

The Phoenix can also be found in the writings of Roman historians and mythographers, who relied heavily on Greek sources.

Ovid's Metamorphoses[]

A Roman wall painting of a Phoenix, preserved from the city of Pompeii, which was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 79 CE. Currently located in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, Italy.

Ovid was a famous Roman poet who lived sometime around the first century BCE until sometime around the first century CE. His most famous work was his retelling of Greek myths, called "Metamorphoses," since each story in the collection revolves around the idea of some sort of transformation. In the fifteenth book of Metamorphoses, Ovid relays a story of the Phoenix which is said to be from Pythagorus:

| “ | Yet these creatures receive their start in life from others: there is one, a bird, which renews itself, and reproduces from itself. The Assyrians call it the phoenix. It does not live on seeds and herbs, but on drops of incense, and the sap of the cardamom plant. When it has lived for five centuries, it then builds a nest for itself in the topmost branches of a swaying palm tree, using only its beak and talons. As soon as it has lined it with cassia bark, and smooth spikes of nard, cinnamon fragments and yellow myrrh, it settles on top, and ends its life among the perfumes.

-Ovid, Metamorphoses XV (391-417)[6]

|

” |

Ovid's account is fairly similar to the account given by Herodotus, but adds small details, such as the Phoenix's diet being composed of incense and sap, the tree that the Phoenix dies and then is reborn on being a tall palm tree, and the addition of cinnamon and other fragrant plants to the Phoenix's pyre.

The Phoenix in Medieval Christian Bestiaries[]

Medieval bestiaries were not naturalistic or scientific descriptions of animals, like what one would expect from a modern encyclopedia. Instead, their purpose was theological. Bestiaries were collections of moral and symbolic stories about animals, plants, and sometimes stones which served to show how all of the natural world is part of God's creation.

The Aberdeen Bestiary[]

An image of the death of the Phoenix found on folio 56r of the Aberdeen Bestiary (12th Century CE).

The Aberdeen Bestiary is a bestiary from 12th century England. The entry for the Phoenix begins as follows:

| “ | [Of the phoenix] The phoenix is a bird of Arabia, so called either because its colouring is Phoenician purple, or because there is only one of its kind in the whole world. It lives for upwards of five hundred years, and when it observes that it has grown old, it erects a funeral pyre for itself from small branches of aromatic plants, and having turned to face the rays of the sun, beating its wings, it deliberately fans the flames for itself and is consumed in the fire. But on the ninth day after that, the bird rises from its own ashes. | ” |

Within this bestiary, the Phoenix is considered to be a fantastical bird from Arabia, which may have seemed like a far off and exotic land to medieval Europeans. The Phoenix is said to be purple in color based off of its name. This is because the pigment Tyrian Purple, also known as Phoenician Purple, was first produced in the city of Tyre in Phoenicia.[9] Tyrian purple was difficult to produce, being a pigment extracted from shellfish, but was resistant to fading over time.[9] As such, it was very expensive and highly valuable.[9] Due to this, Tyrian Purple was often associated with royalty, and in later periods, the Roman empire itself.[9] This color therefore gives the Phoenix regal associations.

The Phoenix is considered to be a single creature, rather than being a species with multiple individuals, making the Phoenix unique and one-of-a-kind. It has an extremely long lifetime, living longer than five hundred years. When its life cycle comes to an end, it gathers pleasant-smelling aromatic plants and creates itself a funeral pyre. It then faces the sun- a nod to the Phoenix's ancient association with the Greek god Helios and the Egyptian god Ra- as it fans the flames of its pyre and is consumed by flame. But then, after nine days, it regenerates. This cycle of death and resurrection caused medieval Christians to associate the Phoenix with Jesus Christ, with the author associating the aromatic plants with the Old Testament (also known as the Hebrew Bible), and the New Testament of Christianity:

| “ | Our Lord Jesus Christ displays the features of this bird, saying: 'I have the power to lay down my life and to take it again' (see John, 10:18). If, therefore, the phoenix has the power to destroy and revive itself, why do fools grow angry at the word of God, who is the true son of God, who says: 'I have the power to lay down my life and to take it again'? For it is a fact that our Saviour descended from heaven; he filled his wings with the fragrance of the Old and New Testaments; he offered himself to God his father for our sake on the altar of the cross; and on the third he day he rose again.

-Aberdeen Bestiary, folio 55v[8] |

” |

The author also gives an alternate interpretation of the Phoenix, where the Phoenix represents the Christians who will be resurrected during the final judgement, with the sweet-smelling aromatic plants representing the virtues that the saved had gathered in life:

| “ | The phoenix can also signify the resurrection of the righteous who, gathering the aromatic plants of virtue, prepare for the renewal of their former energy after death.

-Aberdeen Bestiary, folio 55v[8] |

” |

At the time the Aberdeen Bestiary was written, it had been roughly a century since the first crusades attempting to take the Holy Land from the Muslim Arabs had begun. As such, these tensions between Christians and Muslims are apparent within the text. Within this bestiary, the Arabs, as a Muslim people, are considered to be "unsaved" by the author, and therefore "of this world" as opposed to "the world to come" after the final judgement. The author associates the Phoenix with those who have separated themselves from the vices of the world and turned themselves toward the transcendent virtues of Christianity:

| “ | The phoenix is a bird of Arabia. Arabia can be understood as a plain, flat land. The plain is this world; Arabia is worldly life; Arabs, those who are of this world. The Arabs call a solitary man phoenix. Any righteous man is solitary, wholly removed from the cares of this world.

-Aberdeen Bestiary, folio 55v[8] |

” |

The Phoenix is not considered by the author to be merely the product of fanciful stories and traveller's tales. Instead, the author considers the Phoenix to be a real flesh-and-blood creature, and goes into detail about the process it goes through to regenerate itself: starting as a fluid, then a worm, and eventually back to its glorious bird form. The author sees the real existence of this creature as objective proof of the resurrection of at the final judgement:

| “ | The phoenix also is said to live in places in Arabia and to reach the great age of five hundred years. When it observes that the end of its life is at hand, it makes a container for itself out of frankincense and myrrh and other aromatic substances; when its time is come, it enters the covering and dies. From the fluid of its flesh a worm arises and gradually grows to maturity; when the appropriate time has come, it acquires wings to fly, and regains its Previous appearance and form. Let this bird teach us, therefore, by its own example to believe in the resurrection of the body; lacking both an example to follow and any sense of reason, it reinvents itself with the very signs of resurrection, showing without doubt that birds exist as an example to man, not man as an example to the birds. Let it be, therefore, an example to us that as the maker and creator of birds does not suffer his saints to perish forever, he wishes the bird, rising again, to be restored with its own seed. Who, but he, tells the phoenix that the day of its death has come, in order that it might make its covering, fill it with perfumes, enter it and die there, where the stench of death can be banished by sweet aromas?

-Aberdeen Bestiary, folio 55v, 56r, 56v[8] |

” |

The author then implores his audience to, like the Phoenix, shed away their old, sinful life, and be reborn in Jesus Christ- associating the aromatic plants this time with the sweetness of martyrdom:

| “ | You too, O man, make a covering for yourself and, stripping off your old human nature with your former deeds, put on a new one. Christ is your covering and your sheath, shielding you and hiding you on the evil day. Do you want to know why his covering is your protection? The Lord said: 'In my quiver have I hid him' (see Isaiah, 49:2). Your covering, therefore, is faith; fill it with the perfumes of your virtues - of chastity, mercy and justice, and enter in safety into its depths, filled with the fragrance of the faith betokened by your excellent conduct. May the end of this life find you shrouded in that faith, that your bones may be fertile; let them be like a well-watered garden, where the seeds are swiftly raised.

-Aberdeen Bestiary, folio 56v[8]

|

” |

Guillaume le Clerc de Normandie's Bestiaire[]

Guillaume le Clerc de Normandie was a Norman cleric from the 13th century CE. His account of the Phoenix, found in his work Bestiaire, is similar to prior accounts, other than instead of being a bird from Arabia, Guillaume places the Phoenix in India. India would have been even more of a remote location to Europeans at the time than Arabia, which may have begun to lose its mythic wonder after centuries of crusades. Also, instead of Heliopolis, Guillaume's Phoenix travels to a city called "Leopolis," though the two cities may be one and the same:

| “ | There is a bird named the phoenix, which dwells in India and is never found elsewhere. This bird is always alone and without companion, for its like cannot be found, and there is no other bird which resembles it in habits or appearance. At the end of five hundred years it feels that it has grown old, and loads itself with many rare and precious spices, and flies from the desert away to the city of Leopolis. There, by some sign or other, the coming of the bird is announced to a priest of that city, who causes fagots (wooden sticks) to be gathered and placed upon a beautiful altar, erected for the bird. And so, as I have said, the bird, laden with spices, comes to the altar, and smiting upon the hard stone with its beak, it causes the flame to leap forth and set fire to the wood and the spices. When the fire is burning brightly, the phoenix lays itself upon the altar and is burned to dust and ashes. Then comes the priest and finds the ashes piled up, and separating them softly he finds within a little worm, which gives forth an odor sweeter than that of roses or of any other flower. The next day and the next the priest comes again, and on the third day he finds that the worm has become a full-grown and full-fledged bird, which bows low before him and flies away, glad and joyous, nor returns again before five hundred years.

-Guillaume le Clerc, Bestiaire[10] |

” |

Gallery[]

See also[]

In some Christian and occult traditions, there is a demon called "Phenex" who takes the form of the Phoenix.

References[]

- ↑ https://www.gutenberg.org/files/782/782-h/782-h.htm

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 https://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/Phoinix.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 http://vr.theatre.ntu.edu.tw/hlee/course/th6_520/sty_egy/minor/phoenix.htm

- ↑ http://www.seaturtle.org/PDF/PottsDT_2001_InUnitedArabEmiratesANewPerspective_p28-69.pdf

- ↑ https://recentlyextinctspecies.com/pelecaniformes-egrets-herons-ibises-pelicans-shoebills-etc/ardea-bennuides

- ↑ https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph15.htm

- ↑ https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/ms24/f55r

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/ms24/f55v

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 https://www.worldhistory.org/Tyrian_Purple/

- ↑ https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13220/13220-h/13220-h.htm#BESTIARIES_04